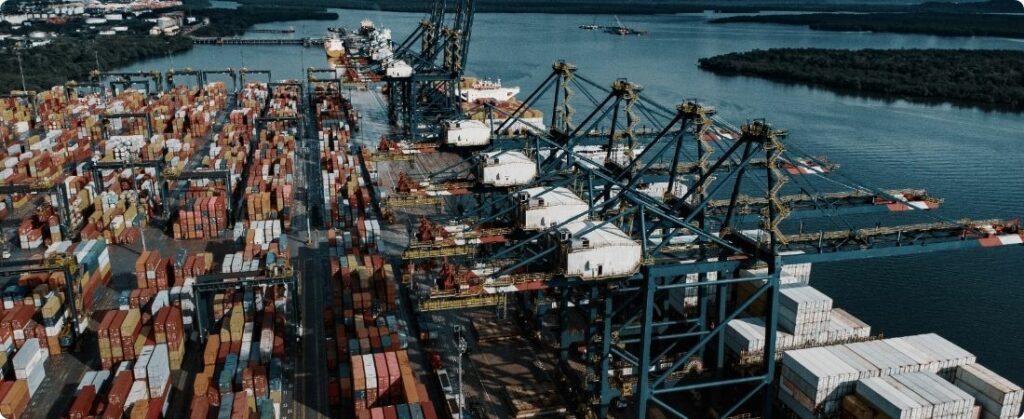

The largest port complex in Latin America, the Port of Santos accounted for 29% of the Brazilian trade flow in 2024, moving US$ 174.43 billion, according to the Port Authority. Although the title is impressive, it faces an almost chronic problem: queues of ships that delay entries and departures, an issue that worsened during the pandemic and has not yet returned to pre-crisis levels.

Delays gain national scale

The bottleneck is not exclusive to Santos. Across Brazilian ports, only 23 % of 2024 shipments were on time. For goods such as soybeans, the average loading time jumped from 10.5 to 17.5 days between February 2024 and the same month in 2025. This is a systemic phenomenon that begins at the origin of the ship's call and propagates to the final destination.

Inside the causes

To Michelle Aguirre, export manager at AD Shipping, the origin of the delays is multiple. First, the capacity of the terminals: Brasil Terminal Portuário (BTP) operated at 95 % in 2024, when international studies recommend 70 % as a safe limit. Santos Brasil and BTP operated at 76 % and 73 %, respectively, above the level of 65 % that guarantees a margin for unforeseen events.

Furthermore, the depth of the canal remains limited. Even with periodic dredging, the draft does not allow large ships to enter full, forcing them to reduce their load and increase the docking time. To top it all off, the Anchieta-Imigrantes system, the main road artery for trucks, frequently gets blocked, forming a vicious cycle: the ship is delayed, the yard fills up, the truck does not enter — and vice versa.

Accounts that don't add up

When the clock stops, the bill arrives. Demurrage costs (container stopped at the terminal) and detention (container held beyond the deadline by the exporter/importer) can exceed the value of the cargo. Freight variations, boosted by geopolitical crises such as the Red Sea, adds another layer of unpredictability.

The coffee sector illustrates this well: in January 2025 alone, delays, changes in schedule and cargo rollovers resulted in R$6.1 million in additional expenses. In the previous eight months, the accumulated loss reached R$57.7 million. Even worse, the coffee that was not shipped in January cost the country US$226.05 million in foreign currency — money that also stops circulating in the hands of producers.

What's (finally) changing

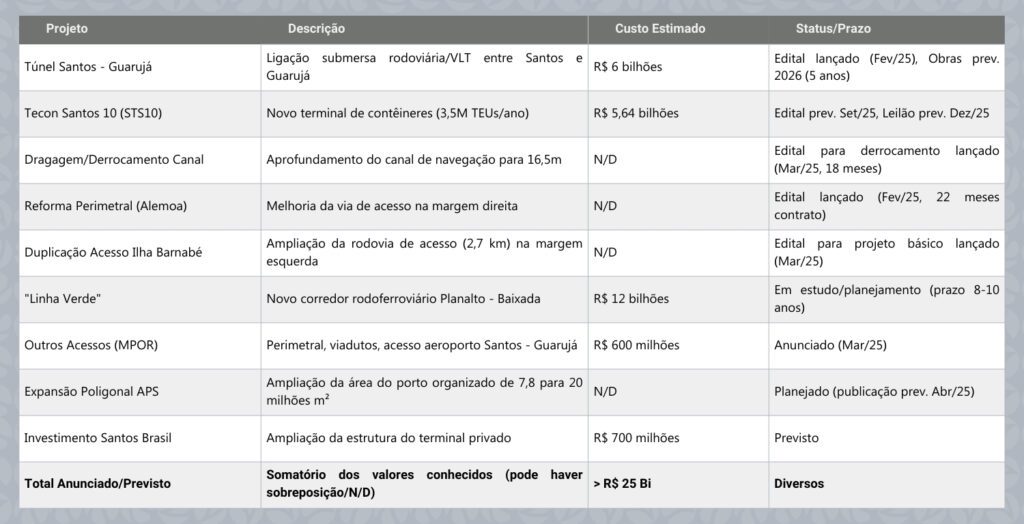

On the one hand, infrastructure projects are moving forward: dredging to 16 m, widening of berths at Tecon Santos and BTP, new viaduct at the Anchieta access point (2025-26). On the other hand, the government launched Navegue Simples (Decree 12.078/24), a program that cuts red tape in authorizations and leases, reducing concession deadlines by up to 40 %. There are also automation initiatives: Santos Brasil already operates cranes by remote control, while other terminals are racing to keep up.

Vision of the future

Experts agree that there is no single solution. Access, capacity and technology must be tackled together, making Brazilian terminals attractive to new routes and fleets — a condition for alleviating the backlog and regaining predictability.

How your company can react now

While the infrastructure is not fully adjusted, those operating in foreign trade need to closely monitor the ends of the chain, renegotiate demurrage/detention clauses and plan shipping windows well in advance. If you want to understand which alternatives are suitable for your cargo flow, talk to our experts: we can map specific bottlenecks and suggest route, contract or storage adjustments that preserve margin and deadline.